The world has watched as Japan first took a very low-key approach to the coronavirus pandemic and then, more recently, has stepped up its efforts to aggressively confront the threat. Japan was one of the first countries to be faced with large numbers of infected patients, both from the cruise ship the Diamond Princess and then as more Japanese citizens fell sick through exposure to tourists from China and other vectors. Overall it seemed to face down these threats through a strategy that was not entirely clear to outside observers but involved face masks, requests for people to limit exposure to others, and an emphasis on contact tracing. Beyond these limited measures, the government seemed to emphasize carrying on business as usual, and eschewed the kinds of restrictions on personal movement adopted by other countries. Even while that has changed and Prime Minister Abe has declared a nation-wide state of emergency from April 16th to at least May 6th, the actions taken are nowhere near as strict as those in many other countries.

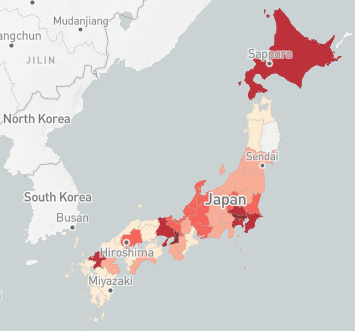

Much as in the United States, responses across Japan have been left to the prefecture and local governments, resulting in a patchwork of policies and guidelines among jurisdictions, boards of education, and other entities. This was exacerbated initially when the prime minister declared a state of emergency in only seven of the 47 prefectures, including the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, but left surrounding prefectures to follow guidelines issued theretofore. This had some areas issuing formal requests for people to stay home, and at least to avoid “the 3 Cs”, places that are “crowded, closed, and involve close contact”, while others simply advised people to stagger commute times, work from home if possible, and avoid unnecessary travel – advice many people seemed to ignore. As in other countries, this also seems to have compelled some people to leave the more restricted areas and return to their hometowns or travel to stay in outlying areas for the duration, potentially taking the virus with them.

Response to the coronavirus in Japan is guided by what is commonly referred to as the Special Measures Act (特別措置法 or 特措法 for short), granting the Prime Minister the authority to authorize prefecture governors to implement special measures in order to respond to the Covid-19 crisis. This law is an updated version of the 2012 Act on Special Measures for Pandemic Influenza and New Infectious Diseases Preparedness and Response, which was itself created in response to lessons learned during the 2009 swine flu pandemic. This has been amended to cover the Covid-19 coronavirus, which was not included in the types of disease listed in the original law.

The law authorizes the Prime Minister to declare a state of emergency in designated prefectures if an outbreak of a heretofore unknown disease is deemed to present a substantial danger to the health and well-being of the people, although the definition of what this would be is left vague, with no numerical tripwires. The Prime Minister is advised by a panel of experts assembled to provide guidance in responding to the situation, both prior to and following any declaration. Even without the law, governors had the ability to request certain actions from residents and respond to emergencies to a degree. However, based on lessons learned in previous emergencies, especially in 2009, the law was crafted to address various shortcomings identified in responding to those, including setting standards for prefecture and local governments to decide when to close schools, strengthening the ability of officials to carry out a number of necessary measures to address the crisis, and enabling better, more streamlined communications and coordination among entities. Among other provisions, the law authorizes planning and preparedness measures for a pandemic emergency and it mandates that governments make efforts to inform the public about these. The Prime Minister’s Office and relevant ministries can issue directives and guidelines for responding to the crisis, but the adoption and implementation of specific policies are left to the prefecture governors. The law also authorizes governors to establish their own advisory panels. One further benefit of the emergency declaration is that it’s seen as conferring greater urgency and authority on them to carry out those measures, hopefully facilitating compliance by residents.

Perhaps the greatest difference between the authority conferred on the governors in Japan as compared to the executives in other countries is the lack of their ability to order a “lockdown” or “stay-at-home” measure. The law does authorize the requisitioning or seizure of property necessary to respond to an emergency, along with other inspection and enforcement measures, and there are penalties attached to non-compliance.

However, when it comes to individual actions and movements, governors can only “request” compliance (要請) or, if this proves ineffective, “direct” it (指示). Significantly, though, no penalties attach to these, and what recourse the governors have is unclear beyond appeals to public pressure on non-compliers. The lack of enforcement measures with penalties arises from the decision made in crafting the 2009 law to rely on educating the public and gaining their voluntary compliance, hence the requirement for plans to be publicly disseminated. This was because policy-makers determined willing compliance was more desirable and that forced compliance would be extremely difficult logistically, given the need to mobilize and coordinate multiple agencies to carry it out.

Specifically, the law gives governors the authority to request that residents refrain from leaving their home except for necessary errands, exercise, or work that cannot be carried out at home. They can also request that places where people congregate such as schools, public spaces, entertainment venues, and other facilities impose limits on or cease entirely their activities, and it further gives governors the ability to direct them to do so if they do not comply with the initial request. This stops short of an order with enforceable penalties, however.

One issue that has arisen concerns businesses asked to reduce or suspend their activities. The law requires compensation for requisitioned goods and property, but there are no provisions for compensation for complying with requests to scale back or cease operations. This would help increase compliance and would align with efforts in other countries to alleviate the economic damage from shutdown measures, but the necessary expenditures are a political decision and can make it more difficult for a government to resort to these policies and allocate budget for them.

Authorities do have the ability to temporarily shut down roads or businesses should they be connected to a cluster of infection, but this is a very limited control measure and does not allow for such draconian actions such as sealing off access to entire cities or forbidding all travel, such as was seen in China. This power is conferred by the Infectious Diseases Control Law, which governs the specific response to outbreaks of infectious disease (as opposed to the Special Measures Act, which governs large-scale efforts to contain any such outbreak).

Even with the fairly limited extent of powers conferred by it, there has still been at least some debate about the constitutionality of the Special Measures Act.

Specifically, beyond a certain common level of distrust seen in other countries concerning potential abuses of such special powers by those who wield them, many Japanese are wary due to the ways in which government authority was used in the years leading up to and through World War II to crush dissent and restrict information and activities that might run counter to the interests of the leadership, particularly under the 1938 National Mobilization Law. This is despite the changes made to the Japanese Constitution in the postwar phase, including the addition of Chapter 8 on local self-government, which was part of an effort by the Americans writing the new constitution to disperse authority and provide countervailing centers of power to the central government by strengthening the autonomy of prefecture and municipal governments.

The structure of the law, with power being delegated to governors, is partly a reflection of this dispersal of authority and partly an acknowledgement of the fact governors are far better equipped to respond to the specific circumstances in their individual prefectures.

There does not appear to be any serious movement to strengthen the existing law, and that is probably not likely unless it ends up being wholly inadequate to the needs of the current situation, which is still unclear. If there were calls to revise it, any expansion of powers would almost certainly involve addressing challenges based on constitutionally mandated protections on civil liberties ensuring freedom of assembly, personal property, and other rights. It’s unclear how restrictions on these would balance out with other powers given to the government to ensure and protect the lives and wellbeing of citizens.

One interesting note is the actions taken by the prefecture of Hokkaido in February to counter an early outbreak of the virus there. With existing powers available to the governor prior to the Prime Minister’s declaration of a state of emergency later in March, schools were closed, large-scale gatherings were cancelled, and people were encouraged to stay home. Within a few weeks, the spread of infection was brought under control enough to begin reopening social and economic activity. This indicates that authority to address serious public health issues does already exist normally. However, national coordination and resources can be better brought to bear under the Special Measures Act, as noted above. (In a cautionary note, Hokkaido has had to reimpose restrictions after a resurgence of the virus.)

It can be argued that response has also been hindered by an intentional effort to restrict access to testing, ostensibly to avoid overwhelming the health care system, since people testing positive must by law be admitted to a hospital. Testing is hampered by very strict requirements that applicants have had a high fever for at least five days, low blood oxygen, etc. One factor is a recognized lack of testing facilities that is only beginning to be addressed, along with an effort to expand care capacity through housing less seriously ill patients in hotels, as was done in China. Anecdotally, there have been many reports of people unable to get tested even with apparent symptoms of Covid-19. As with the United States, which also suffers from limited access to testing, lack of clear understanding of the extent and nature of the virus means policymakers are essentially working blind in trying to understand the scope of the problem and effectively address it.

Fears of overwhelming the medical system are well-founded, since Japan has an acknowledged shortage of doctors when taking into consideration its aging population and the large number of medical facilities they’re spread among. Furthermore, despite statistics showing Japan having far more hospital beds available than many other advanced countries, many of these are in small-scale neighborhood hospitals or clinics that are not set up to provide advanced treatment. Reports are becoming more common of coronavirus patients being turned away from many of these hospitals due to the inability to provide appropriate care for them. This then results in their being directed to larger hospitals where they are also turned away because of a lack of open beds. In one case, an ambulance was reportedly turned away from 80 hospitals before finally being admitted, and another where paramedics contacted 40 facilities before finding a hospital willing to take a patient.

Other bureaucratic and cultural obstacles to efforts to reduce crowding and exposure to the virus have also played a role, as have been well-reported, such as resistance to allowing employees to work from home, or that staff who are able to work from home still report to the office once or twice a week to take care of paperwork. It appears these are being slowly addressed over time, however.

On the most fundamental level, though, in mounting a national response to the crisis there has clearly been a political unwillingness to incur the economic damage that would result from a more strictly enforced policy of discouraging movement even under the current law. The US and other countries are wrestling with this calculus, and some countries have opted for approaches that do even more than Japan to favor the economic side of the equation, Sweden being perhaps the premier example of non-restrictive measures. It remains to be seen if Japan’s combination of voluntary public compliance, focused testing, and limited centralized coordination of response will be effective in blunting the worst of the pandemic and minimizing the cost to the country in both human and economic terms.

Matthew Gillam

April 28, 2020