Background

The popular image of New York City, aside from Central Park, is usually of towering office buildings in Manhattan or densely packed brownstones in Brooklyn. In reality, though, there are considerable amounts of open land in the five boroughs, not all of which is parkland. Increasingly, some of this land harkens back to a time when the city had many working farms and grew much of its own food. Now, however, growing food is about much more than simply growing food.

New York City was formed through the consolidation of numerous scattered cities, towns, and villages in 1898. For most of its history, large parts of the area that became the city were occupied by working farms and smaller kitchen gardens, until these gradually were replaced by buildings or simply left fallow because they ceased being profitable as transportation technology allowed food to be shipped in from greater distance at lower cost.

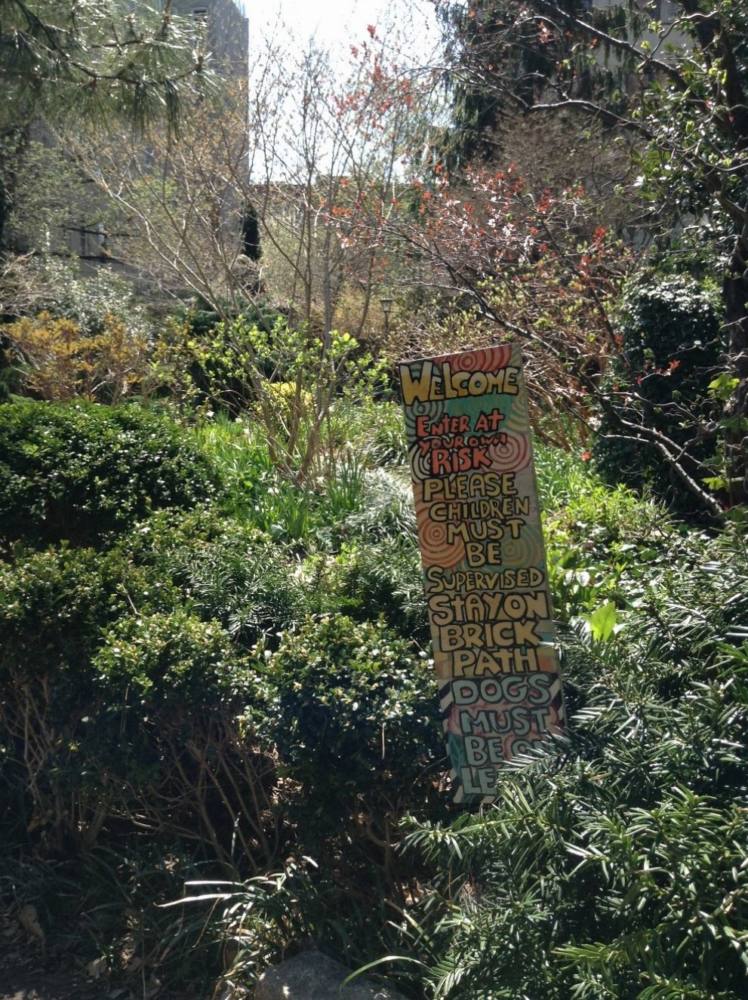

Most of what could be termed “urban agriculture” in the city from the late 20th century until now, however, began with the collapse of the city’s finances and exodus of large numbers of residents that became seriously apparent from the 1960s. Scattered areas of open land began to proliferate as buildings were abandoned for lack of rent-paying tenants and were then burned down, either through simple arson or for the insurance money, or left to decay until being seized and torn down by the City. These vacant lots filled with trash and attracted drug dealers and users, as well as contributing to a general feeling of insecurity, so that the remaining residents began to think about how to reclaim them, clean them up, and use them for the benefit of the neighborhood. “Guerilla gardeners” began “seed bombing” lots by throwing paper bags with coffee grounds, compost, and seeds over the fences, and they began to actually move in to clear trash and create gardens with plant beds, paths, and other amenities.

The City, especially through the Parks Department, institutions such as botanic gardens, and other groups gradually became involved in supporting these gardens, laying the basis for entrepreneurs to come along in recent years with larger projects like Brooklyn Grange and Gotham Greens that are working to find ways to return true, sustainable, large-scale, for-profit agriculture to New York City.

Unlike traditional agriculture, urban agriculture in all its modern forms is not simply about raising food for personal use or profit. It is also about strengthening communities, teaching people about nutrition, nature, job skills, and activism – how to act to take control of your life and your environment. It’s also about learning to live in a more sustainable manner.

Community Gardens and Their Backers

As noted above, there are basically two categories of urban agricultural operations these days in New York City. One is comprised of the volunteer-based, usually not-for-profit community gardens, and the other of for-profit, primarily production-focused “farms”. There is not always a clear distinction between community and for-profit, since both tend to sell their products through greenmarkets or Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) arrangements, have education and community outreach operations, and see their role as more than simply growing fresh produce. This post will talk about community gardens and some of their support mechanisms, while a following post will look at the newer for-profit urban farming operations.

NYC Department of Parks and Recreation: GreenThumb

GreenThumb is the office within Parks that is primarily responsible for overseeing community gardens and other greening initiatives in New York City. They currently work with about 550 community gardens ranging in size from roughly 1,000 square feet to their largest, which is five acres in size.

According to Bill LoSasso, Director of GreenThumb, about 400 of the community gardens they oversee are located on Parks Department property and are considered semi-permanent, 10 to 12 are on Department of Transportation, Department of Environmental Protection, or other City-owned property, and roughly 150 are run by privately-owned land trusts, such as New York Restoration Project(https://www.nyrp.org/).Gardens in the GreenThumb program agree to a set of rules and operating procedures guiding their governance structure, public accessibility, and other activities, and are subject to quadrennial review of their compliance. As long as they are considered to be adhering to their agreement with GreenThumb their license is almost certain to be renewed every four years, protecting their right to exist and making them eligible to work with and receive support from various City agencies. Most importantly, NYC does not have or require any zoning designation for gardens or agriculture, meaning there are no restrictions on where these activities can take place. Mr. LoSasso cited this flexibility as an important factor in allowing the kind of community and individually led initiatives that have transformed neighborhoods through agriculture. He also explained the process whereby GreenThumb can work with people who wish to turn a piece of unused or abandoned City-owned land into a community garden, negotiating with other City agencies to have the land transferred to GreenThumb for use by the community. He said these conversations have changed (becoming easier) since Hurricane Sandy, with the increased emphasis on developing greater sustainability and resiliency through green infrastructure. He also noted greater awareness of the importance of gardens for community development, for a number of reasons, saying that now the word “community” is just as important as the word “garden”.

GreenThumb has a community garden locater on its website for the gardens in its program:http://www.greenthumbnyc.org/gardensearch.html. It’s interesting to note that they tend to cluster in many of the residential neighborhoods that have struggled most with socio-economic challenges over the past few decades, but where a strong sense of community clearly survives.

GrowNYC

GrowNYC is a 501c3 nonprofit corporation, originally established by Mayor John Lindsay in 1970 as a think tank to address environmental issues facing New York, functioning in partnership with the City but independent from it. Its mission has changed over the years, and now it takes a more hands-on role, running the system of greenmarkets for the City as well as supporting community gardens, recycling efforts, and a variety of education initiatives. The greenmarket system extends for hundreds of miles away from the city, and only a few participants are actually producing their products within the five boroughs.

Working with GreenThumb, GrowNYC has helped build over 90 community gardens and supports hundreds more through providing technical assistance, green infrastructure projects, volunteers, and other valuable services. They also support the Grow to Learn program in collaboration with the Department of Education’s Office of School Food and GreenThumb, helping create gardens in public schools across the city.

Botanic Gardens

The Brooklyn Botanic Garden (https://www.bbg.org/) has developed a number of programs supporting community gardening and greening throughout the borough. According to James Harris, Director of Government and Community Affairs, BBG coordinates the Community Garden Alliance in Brooklyn, which includes over 130 community gardens, and provides members with services such as technical assistance, networking support, workshops, and an annual conference. They also run a ‘train the trainer’ program called BUG, the Brooklyn Urban Gardener Certificate Program, which promotes sustainability and community greening through a free ten-week course requiring 30 hours of community greening and a team project. The hope is that graduates of this program will then go out into their communities and train others in these skills while helping their neighbors with their gardening and greening efforts. BBG’s Greenest Block in Brooklyn Contest and Street Tree Stewardship Initiative also encourage communities and individuals to take an active role in making their streetscapes green and welcoming.

All of these programs can be found directly at https://www.bbg.org/community/.

The New York Botanical Garden (http://www.nybg.org/home/), in the Bronx, also provides similar support services for community gardens and greening efforts in that borough through their Bronx Green-Up program (http://www.nybg.org/green_up/index.php), and has been instrumental in helping community efforts since 1988 to create and improve the gardens that have contributed to the incredible renaissance experienced by the Bronx over the last 30 years or so.

New York City Community Garden Coalition

While community gardens clearly contributed to the revival of New York City by providing oases of green and community activity, making neighborhoods more attractive, they were almost victims of their own success as the city showed signs of recovery from the 1990s onward.

The NYC Community Garden Coalition was formed in 1996 to serve as a collective voice opposing efforts by then Mayor Rudolph Giuliani to take back garden land owned by the City and sell it, as people started moving back into the city, demand for housing grew, and property values began to increase. Having been an integral player in reaching an agreement with the City on preserving many, though not all, of the gardens, the coalition continues to act as an advocate for community gardens throughout the city. One program they are currently involved in is their Gardens Rising project, to help reduce storm water run-off on the Lower East Side.

A good, though somewhat one-sided overview of this difficult period for many community gardens is available on their website at http://nyccgc.org/about/history/.

Finally

Of course, the efforts of all of these programs would be meaningless without the work put in by individuals and groups in neighborhoods around the city, literally taking matters into their own hands, creating and preserving gardens and green spaces that benefit their communities. To a large extent, government and other institutions only eventually came to recognize the value of these volunteer activities and played catch-up in developing programs to support them.

Matthew Gillam

April 2017